Defining Connection in the Baseball Swing: Moving Beyond the Golf-Based Model

By Ken Cherryhomes ©2025

Introduction

The term connection in swing mechanics has become a widely used but often misunderstood concept in baseball and softball swing analysis. Originally rooted in golf, the idea of connection was developed around maintaining a fixed club-to-body relationship to optimize swing efficiency. However, when this concept was applied to baseball, it led to a model that does not fully account for the dynamic, reactive nature of hitting.

Companies like Blast Motion have attempted to quantify connection with sensor-based swing metrics, defining it as a bat-to-body angle relationship. This approach assumes that a consistent 90-degree bat-to-body angle improves efficiency and repeatability in a hitter’s swing. However, this rigid interpretation creates problems when applied to baseball, where adaptability and real-time adjustments are crucial.

This article will break down:

- The origins of connection in golf.

- How Blast Motion applies the concept to baseball and softball.

- The fundamental flaws in applying a static connection model to a dynamic swing.

- A physics-based definition of connection that objectively governs swing efficiency.

Origins of Connection in Golf and Its Application to Baseball

In golf, connection refers to maintaining a synchronized relationship between the arms, club, and body throughout the swing. Since the golf ball is stationary and the golfer operates within a fixed stance, maintaining a repeatable arm-body relationship is crucial for clubhead accuracy and efficient energy transfer. This is why a 90-degree angle between the lead arm and torso at the start of the downswing is considered mechanically sound in golf.

In contrast, baseball and softball require hitters to react to a moving ball that varies in speed, location, and movement. Despite this, Blast Motion adapted the golf-based definition of connection, assuming that an optimal swing follows a similar bat-to-body relationship. Their system evaluates connection using two primary metrics:

- Early Connection – the angle between the bat and the batter’s torso at the start of the downswing.

- Connection at Impact – whether the bat maintains a consistent vertical angle in relation to the body at contact.

Blast Motion scores a hitter’s connection based on how closely their bat-to-body angle adheres to a predefined ideal, typically around 90 degrees. The assumption is that a higher connection score leads to a more efficient and repeatable swing.

The Problems with the Golf-Based Connection Model in Baseball

While the golf-based connection model works well in a stationary sport, applying it to baseball introduces several flaws:

- Baseball Requires Real-Time Adjustments

Unlike golf, baseball swings must adjust dynamically to different pitch speeds and locations. A rigid 90-degree bat-to-body relationship does not account for the natural variability required in hitting.

- The Strike Zone is Fixed – The Body Shouldn’t Need to Physically Accommodate It

Hitters should establish a stable posture that allows them to cover all pitch locations without altering their body position. Instead of tilting their torso to reach low pitches (as Blast Motion encourages), hitters should maintain consistent posture and let their hands and bat adjust.

- Maintaining Posture Preserves Balance and Adjustability

Great hitters keep their posture and weight distribution stable while adjusting their bat path to different pitch locations. If a hitter alters posture post-launch to maintain a specific connection angle, it can:

- Shift their center of mass, leading to compensatory movements.

- Disrupt balance, hand/eye coordination, and bat path.

This is particularly problematic on low or low-and-away pitches. If a hitter attempts to maintain a rigid 90-degree bat-to-body relationship on these pitches, their torso and center of mass shift forward over the plate at swing launch, disturbing their pre-set posture and balance. To avoid completely toppling forward, the body triggers a compensatory reaction—often shifting the hips or butt back—which throws off energy transfer, delays barrel delivery, and disrupts sequencing. Instead of allowing clean hand and barrel adjustments, the hitter is now forced into recovery mode mid-swing, sacrificing both adjustability and efficiency.

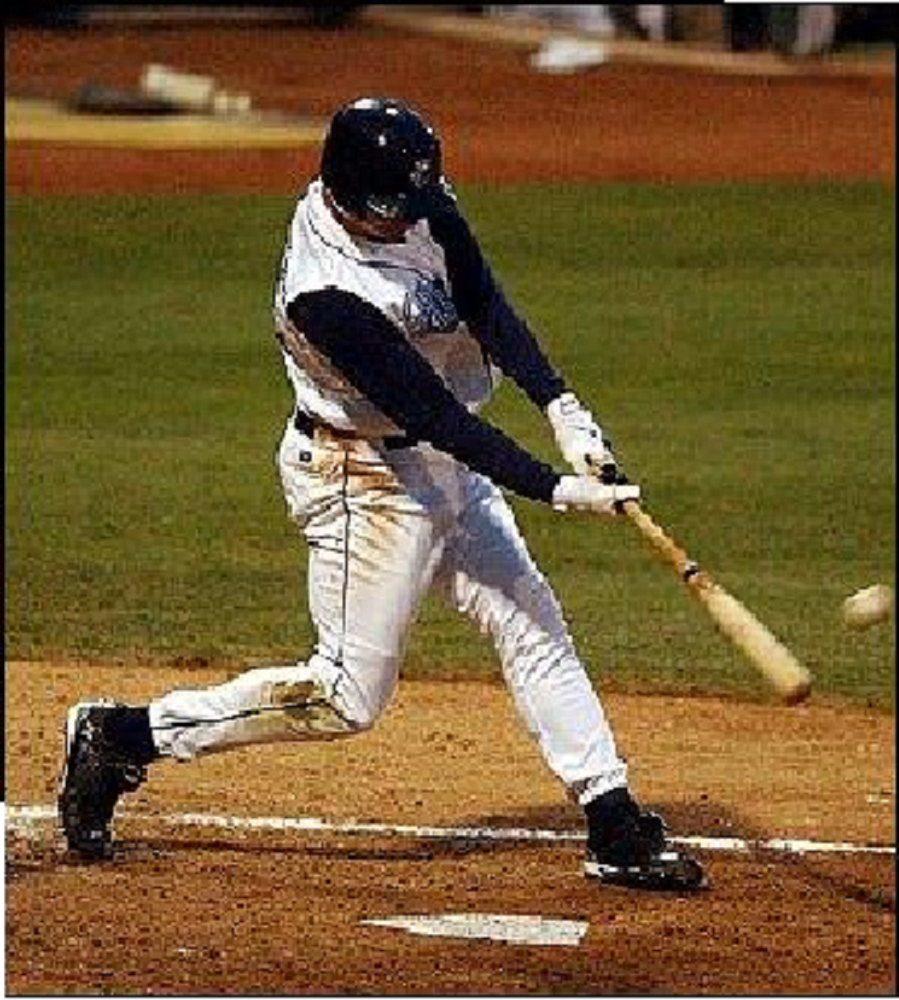

Meeting a low pitch for a home run from the same posture the swing was launched from. Wrist articulation affects the vertical bat angle while maintaining a continuous exchange of energy from the batter to the bat without disruption.

The images provided illustrate batters maintaining posture regardless of pitch height, reinforcing that a well-connected (in respect to kinetic sequencing and energy exchange) swing does not require excessive body tilt to meet low pitches.

- Swing Efficiency is About Energy Transfer, Not a Fixed Bat Angle

Blast Motion’s connection model assumes that a rigid bat-to-body relationship optimizes efficiency. However, efficiency in a baseball swing should be determined by how well energy transfers through the kinetic chain, not by an arbitrary angular measurement. By enforcing a rigid bat angle as an empirical measure of swing efficiency, this system bakes subjectivity directly into what should be an objective evaluation.

Counterarguments to Defenders of the Connected Theory

- The Appeal to Authority Fallacy

- Just because a respected instructor advocates for maintaining a rigid bat-to-body angle doesn’t make it a universal truth demanding obedience. Even elite hitters don’t execute a perfect mechanical model on every swing. Instruction should be based on biomechanical reality, not subjective adherence to a theory that fails under real-world variability.

- Cherry-Picked Video Evidence

- Producing 100 clips of hitters tilting to maintain a 90-degree angle proves nothing if it doesn’t account for why those adjustments were made and how they affected the outcome. The focus should be on total swing efficiency—not just the swings that confirm a theory while ignoring the 1,000s of pop-ups, weak contact, and whiffs resulting from miscalculated barrel arrival due to unnecessary tilt.

- The Flaw of Posture-Induced Barrel Displacement

- When a hitter tilts excessively to maintain 90 degrees, the predicted arrival of the barrel changes—meaning the visual information and timing mechanisms stored in the batter’s memory are now altered.

- The swing is now dependent on compensatory adjustments rather than a stable posture with controlled barrel articulation through the wrists.

- This leads to mistimed contact, pop-ups, and rollovers, which aren’t captured in a highlight reel but are painfully obvious over a full season.

The Difference Between Observation and Scientific Analysis

Like the advocates of the connected theory, I use my powers of observation to study hitters. But the difference is I don’t stop there. Observation without critical thinking is just pattern recognition—it doesn’t prove causation.

They look at a few swings and assume their theory is correct. I look at all swings, including the failures, and ask: Why did this succeed? Why did this fail?

They selectively find clips that confirm their beliefs. I test those beliefs against biomechanics and physics to see if they hold up.

They base their conclusions on mechanical ideals. I base mine on energy transfer, biomechanical efficiency, and adaptability.

Real science doesn’t just look for supporting evidence—it actively tries to disprove itself to see if the theory still holds. That’s why the connected theory collapses when scrutinized under the principles of biomechanics and physics.

A Physics-Based Definition of Connection in the Baseball Swing

True connection in a baseball swing is not about maintaining static angles; it is about optimizing energy transfer through the kinetic chain. This principle follows fundamental laws of physics and biomechanics:

- Energy Transfer Must Be Continuous

A connected swing, by this definition, ensures that force moves seamlessly from the lower body, through the core, and into the bat. Any break in this sequence results in energy loss, reducing power and efficiency or a ‘disconnected’ transfer of energy.

- Rotational Momentum Relies on a Stable Axis

In a well-connected swing, the hitter’s body rotates around a stable axis. Any forward movement (linear displacement) disrupts this rotational efficiency, causing energy leaks.

- Definition of a Disconnected Swing.

If a hitter drifts forward, shifting the batter’s center of mass off axis:

- The generated energy is redirected away from the rotational path.

- Energy transfer to the bat is delayed until connection is reestablished.

- Late compensations are required, reducing bat speed and adjustability.

- Disconnection Leads to Energy Leaks

A disconnected swing occurs when energy is not transferred efficiently, leading to:

- Poor synchronization between the lower body, core, and hands.

- Delayed or mistimed hand activation.

- Loss of barrel control and inefficient bat path.

- Wrist Articulation is Key to Efficient Adjustments

Elite hitters adjust their barrel and attack path through wrist articulation, rather than altering their posture. This ensures that energy is efficiently transferred through the hands into the bat, maintaining a stable and powerful swing regardless of pitch height.

Why Swing Trackers Struggle to Measure True Connection

Bat-mounted sensors, like Blast Motion, attempt to quantify connection by measuring bat angles in relation to body tilt. However, these metrics:

- Do not measure actual energy transfer.

- Fail to distinguish between efficient and inefficient movement patterns.

- Assume that a mechanically “ideal” bat angle equates to an efficient swing, which is not necessarily true.

Why a Physics-Based Definition of Connection is Superior

The golf-based definition of connection assumes that a hitter should maintain a fixed bat-to-body relationship throughout the swing. However, baseball is a reactive sport that requires adaptability, not rigidity. The golf model is designed to minimize adjustability to reduce margin of error, fitting a motor plan built for precision against a stationary object. Unlike baseball, where hitters must adapt to a moving ball in multiple dimensions, golf requires no real-time spatial adjustments.

A physics-based definition of connection recognizes that:

- Swing efficiency is about energy transfer, not a fixed bat angle.

- Balance and posture should remain stable, allowing for independent barrel adjustments.

- Connection is best measured by how well energy is transmitted through the kinetic chain, not by arbitrary angular metrics.

While Blast Motion’s model may offer a structured way to evaluate swings, it ultimately fails to account for the dynamic nature of hitting. True connection in baseball prioritizes efficiency, adaptability, and optimal energy transfer, making it a far more accurate and actionable measure of swing quality.