Misconceptions of Power: The Hidden Pitfalls of Hard-Hit Balls and the Overemphasis on Forward Contact Points

By Ken Cherryhomes ©2025

Introduction:

In the StatCast era, bat speed and exit velocity have become the most celebrated metrics of hitting, often viewed as the ultimate indicators of offensive success. The assumption is simple: the higher the bat speed, the harder a ball is hit, therefore, the higher the likelihood of a positive outcome. However, a closer examination reveals a deeper issue. Among the top 10 hardest-hit balls of the StatCast era, only two resulted in hits—both pulled ground balls. The other eight were pulled groundouts, including three double plays.

This data uncovers a critical flaw in modern hitting philosophies. While exit velocity is lauded, ground balls are rightly demonized for their low success rates, yet the hardest-hit balls are almost always ground balls. The emphasis on exit velocity ignores this shortcoming, leading to a false narrative that hard-hit balls equate to success. But hard-hit balls do not exist in a vacuum. In reality, broadened swing arcs are necessary to pull pitches on outer half of the plate; while producing high exit velocities, it is often at the expense of favorable outcomes. This disconnect reflects the flawed focus on forward contact points and hard-hit balls in today’s hitting philosophies.

Further compounding this issue is how batters’ spatial and temporal memory is being conditioned around this forward contact point centricity. Instead of hunting specific pitch locations conducive to hitting home runs or developing the adaptive swing memory needed for various pitch locations, hitters are reinforcing a narrow success model tied to this aggressive forward contact, as we will explore later in the article. This narrow approach limits hitters’ ability to adjust to different pitch locations, undermining their overall effectiveness.

The Physics Behind Hard-Hit Balls: A False Reflection of Success:

Broadened swing arcs maximize angular velocity, creating impressive exit velocities but often result in ground balls or outs. In the batting cage, maximizing bat speed through a broadened arc often yields positive gains in cage-measured metrics, but this swing doesn’t always transfer well to game situations.

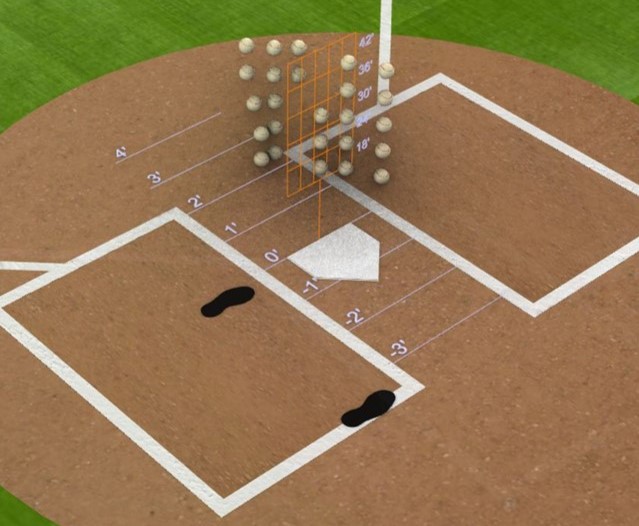

When a batter attempts to pull a pitch on the outer half of the plate, this requires them to meet the pitch at the same contact depth as they would on an inside pitch. The reason is, this contact occurs forward in the swing’s arc, where the barrel has passed the hands and is naturally ascending right before contact. The hitter’s intent is to make contact above the center of the bat’s barrel and below the center of the ball, which is conducive to lifting the ball for home runs. However, due to the broadened arc on outside pitches, and how the barrel ascends as it turns later in its arc, instead it strikes the ball lower on the barrel and above the center of the ball, resulting in a spatial miss and very hard-hit ground ball.

While this broader swing arc generates high exit velocities, it does not guarantee favorable outcomes. Data supports this: many of the hardest-hit balls, despite their high velocities, frequently lead to poor outcomes like groundouts and double plays. This challenges the assumption that exit velocity or hard-hit ball ratings are reliable indicators of success.

The Problem with Forward Contact Point Centricity:

Modern hitting philosophies, especially those that emphasize hitting for power, have fostered a flawed approach where batters chase a specific forward contact point regardless of pitch location. This narrow focus on pulling or lifting pitches creates a success memory and reference point that is biased toward forward contact points on middle-in and inside pitches, leading to struggles on pitches that require deeper contact.

The underlying issue is not just mechanical; it’s a failure in properly training batters’ proprioceptive memory in connection with temporal predictions. Successful swings are not just about timing but also about the precise orientation of the hands and bat at the point of contact. Over time, hitters forge a memory of successful outcomes, with both the timing and bat orientation being essential reference points.

Batters’ proprioceptive systems are being conditioned to expect forward contact points, which biases their internal timing and hand position. This rigid memory of hand and bat orientation limits their ability to adapt to varying pitch locations. Without adaptive proprioceptive training, hitters struggle to adjust to pitches that require different bat angles or contact depths. As a result, they give away outs on pitches outside of their power zones, with only the rare, optimal exception yielding favorable results.

By reinforcing only forward contact points, batters are developing a one-dimensional approach leading to poor performance on pitches that don’t fit their forward-oriented swing pattern.

Rethinking Power Hitting: Hunting the Right Pitch for Maximum Impact:

While power hitting remains a critical component of offensive strategy, there needs to be a refinement in how batters approach different pitch locations. Hunting for pitches that can be pulled and driven for home runs is an excellent strategy when done selectively. However, selling out for power on every swing, especially on pitches that should be met deeper in the swing arc, wind up requiring broader swings, and usually is a losing proposition.

The key is in developing a swing memory that incorporates both spatial and temporal elements, allowing batters to adjust their swing paths and contact points based on the pitch location. Instead of relying on forward contact points for every pitch, batters need to train for deeper contact on outside pitches and recognize when it is appropriate to make contact later in the zone to achieve a better outcome.

Conclusion:

A successful power-hitting approach isn’t just about maximizing bat speed and exit velocity; it’s about managing swing arc breadth, understanding contact points and depths for different pitch locations and selectively hunting the right pitch. While hard-hit balls often grab attention, the data shows that exit velocity alone doesn’t translate to success. Broadening swing arcs to chase power on every pitch, especially outer-half pitches, often leads to suboptimal results.

To truly succeed, batters must refine their swing memory, incorporating spatial and temporal adjustments that allow them to adapt to varied pitch locations. By developing a more flexible approach—one that balances power with adaptability—hitters can maximize their offensive potential, turning selective power into consistent success.