The Torpedo Bat May Not Be for Everyone: Understanding Bat Profiles and Hitter Identity

By Ken Cherryhomes ©2025

Introduction: The Trade We Already Made

The Torpedo Bat has been marketed as a breakthrough, an engineered rebalancing of barrel mass that promises more control, better outcomes, and a feel that flatters otherwise poorly made contact. But underneath the surface metrics and glowing endorsements is a more sobering reality: this bat doesn’t raise the standard. It lowers it.

By shifting mass inward, it aligns performance with failure; specifically, late swings. And where hitters once chased violence at the end of the barrel, the Torpedo Bat trades that violence for comfort. It’s a calculated exchange: leverage for control, whip for manageability.

This isn’t just a new shape. It’s a philosophical shift. And it comes with a cost and with caveats.

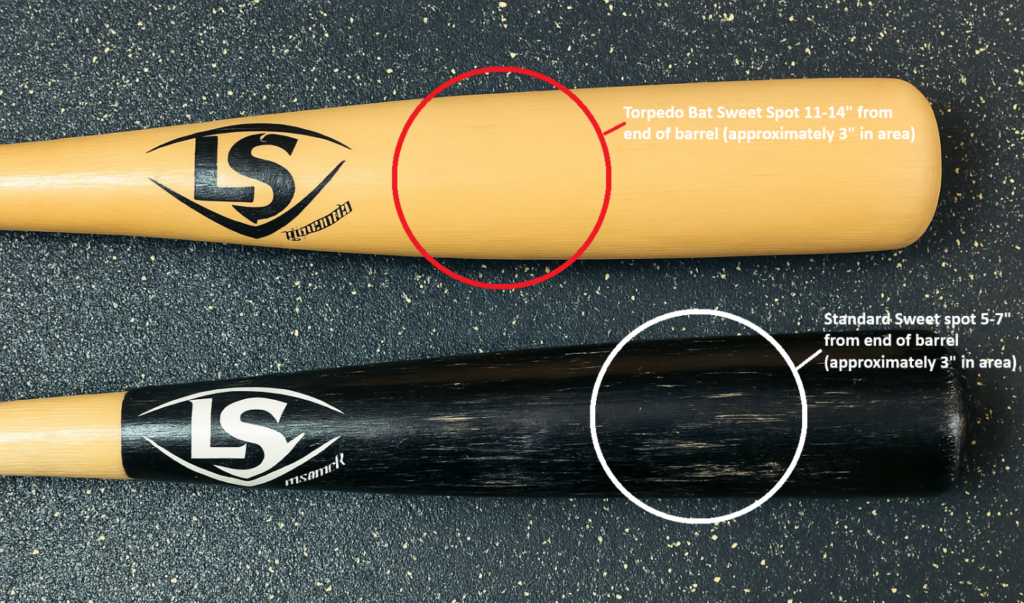

That “frequent” point of contact isn’t optimal. It’s the residue of failure. Specifically, late swings. Before the mass was moved, balls struck at that depth, typically 11 to 14 inches from the end of the barrel, produced poor results. Exit velocity dropped. Weak ground balls and jammed contact were common. That contact zone isn’t where elite hitters drive the baseball. It’s where they fight it off. It’s where barrel control breaks down and outcomes fall apart.

Real innovation doesn’t elevate that zone. It avoids it.

Under controlled constraints, off a tee, in batting practice, or when timing is precise, the point of contact that most often occurs is still the traditional sweet spot. Hitters don’t swing to miss it. They spend their entire careers developing the spatial and temporal awareness to find it. The Torpedo Bat doesn’t meet that standard. It relocates it to where mistimed contact already happens.

It feels like innovation. But it’s not the first time hitters have faced this trade. And it’s certainly not the first time they’ve made their decision.

At the center of the bat debate is a physics principle being ignored in this modern redesign: whip. Not the aesthetic kind, the biomechanical kind. The kind that delivers acceleration late in the swing arc. The kind that turns lag into violence, and violence into exit velocity.

That’s something you create with leverage and mass placed where it can do the most damage—at the last moment. The moment you redistribute that mass inward, the whip starts to die.

Whip vs. Control: What Mass Redistribution Really Costs

Supporters of the Torpedo Bat argue that concentrating mass lower on the barrel, closer to the point of poor but frequent contact, improves control and balances swing speed (quickness) with energy transfer. That’s technically true. But let’s not confuse quickness with velocity, because they are not synonymous. Shifting weight away from the end lowers the bat’s moment of inertia, making it easier to initiate, but it reduces angular momentum, barrel velocity, and potentially, exit velocity.

And in doing so, it removes the very element that power hitters have leaned on for over a century: late acceleration.

Whip is not a byproduct. It’s a weapon. It’s what happens when a hitter stores energy in the lag phase and releases it violently through collision. The more end-loaded the bat, the more potential for whip. Redistribute that weight, and you dampen the violence. You may gain control, but you trade away leverage.

Barrel Identity and Collision Outcome

Historically, hitters have understood this balance intuitively. Take the Louisville Slugger C271, the bat of choice for many power hitters, chosen for its two-and-a-half-inch barrel and end-loaded feel. It’s a weapon in the hands of a hitter seeking damage in the final ten inches of the swing. That profile not only generates whip, it invites tangential collisions, the kind that graze the lower half of the ball and create lift through backspin. Fewer flush hits. More trajectory.

By contrast, broader-barrel bats like the C243 are best suited for line-drive hitters. With more surface area comes more square contact, but fewer of those glancing collisions that generate loft. The bat isn’t designed for backspin as much as it is for contact consistency.

The I13, a hybrid model that combines the handle of the C271 with the larger barrel of the C243, was used by Albert Pujols, who considered himself a line-drive hitter. But Pujols was hardly a textbook example. His career numbers show elite power, high averages, and exceptional barrel control. What his bat choice reflects is how elite pitch selection and a refusal to sell out for power can produce both power and consistency. The I13 offered the surface for flush contact and the mass distribution to drive the ball and gain loft with the right point of contact and bat-ball offset without compromising intent. It was a blend of whip and surface that allowed for adjustability, not just brute force.

And that’s the point. The bat must fit the identity of the swing, not the illusion of comfort.

Matching Feel to Function: A Case Study

When I began working with Jeff Cirillo in the fall of 2004, he was swinging Louisville Slugger G174 and C271 models. They felt good in his hands. But they didn’t match his identity. Cirillo was a line-drive hitter, not a barrel punisher. The G174 and C271 both featured narrow 2.5-inch barrels, ideal for generating whip and tangential collisions, but a poor fit for a hitter who needed flush contact. Without elite power, those glancing collisions didn’t translate to home runs. They translated to fly outs and grounders.

I advised him to switch, not because the bat felt wrong, but because it functioned wrong. Once we realigned his barrel choice to a larger model that suited his hitting goals, the results followed.

The Torpedo Bat’s design alters feel. By shifting weight inward and removing mass from the tip, the bat becomes more balanced than traditional end-loaded models. That tradeoff produces quicker, but not faster, swings and potentially greater control. But it doesn’t erase the physics of collision. More surface and weight concentration near the node may increase the odds of perceived solid contact, but it doesn’t expand the margin for error. And while node relocation may dull the sting, it doesn’t sharpen the swing.

This isn’t theoretical. Redistributing weight away from the end has already been tested for decades with models like the Louisville Slugger M110. Wide adoption of this more evenly weighted bat was swift by certain hitters, not because it promised more surface area or a repositioned sweet spot, but because it offered balance, a lowered moment of inertia, control, and durability.

The M110 had a medium barrel, and evenly distributed mass. The design wasn’t a concession to failure. It wasn’t built to compensate for mistimed swings or flawed decisions. It was made for hitters with compact, precise approaches who valued control over brute force. While its shape is nothing like the Torpedo Bat, both shift the center of mass away from the barrel tip. The result is the same: lower moment of inertia, easier initiation, and more control for a certain swing profile.

The methods differ. The M110 distributes mass evenly. The Torpedo clusters it. But the effect on inertia is similar. And if the vibrational node moves with the mass, the feel of the sweet spot likely moves, too. And when design shifts the sweet spot to match those frequent points of contact, it does more than change feel, it redefines what the hitter experiences as success.

But that’s the problem. These frequent contact points weren’t chosen. They weren’t tactical. They were errors. The byproduct of mistimed decisions. Now they’re being rebranded as “common” and designed around. But when you shift the sweet spot to match a mistake, you’re not helping the hitter find better timing, you’re helping them forget it. Decision-making is a matter of targeting. And timing is the act of delivering the barrel to that target. If the target moves because the design follows failure, then timing itself becomes misaligned. A batter might recalibrate to this new profile, but still make late swing decisions, and now the next layer of misses will land even farther down the barrel. That’s not correction, that’s circular error. At best, you mask the problem. At worst, you train for it.

Designing for the Miss

Meeting some hitters where they are, so to speak, isn’t a solution to a cause—it’s a bandage for a symptom. Because timing will fail. That is the nature of this most difficult thing to do in all of sports. But the answer to failure isn’t to make it feel flush. It’s to train the decision that prevents it.

A bat that masks mistimed contact doesn’t fix the swing. It accommodates it. And the more we normalize tools that soften the penalty for poor timing, the less urgency there is to solve the problem at its source. Timing isn’t just a constraint. It’s the first-order challenge. Design that works around it isn’t progress. It’s surrender.

The Myth of Surface and the Real Loss of Leverage

The Torpedo Bat claims to optimize the tradeoff between surface area and control by moving mass to the most frequent, but suboptimal, point of contact. But it doesn’t solve the flaw that made that contact frequent in the first place. It just makes failure feel flush. This isn’t a better swing. It’s a more tolerable mistake.

And where does that approach stop? At what point does compensating for symptoms become the strategy itself?

More barrel doesn’t mean more power. It doesn’t increase the size of the sweet spot. And it certainly doesn’t add whip. It may offer the illusion of improvement. But without whip, all you’ve done is neuter acceleration and repackage compromise as progress.

And what of early swings? Are they any less common than mistimed late contact? The Torpedo Bat doesn’t solve that problem either. If anything, it doubles down on a flawed approach, masking one type of mistake while ignoring another.

Hitters throughout history have already faced this choice. And they overwhelmingly favored whip, not for comfort, but for consequence. That’s not just preference. That’s performance talking.

Conclusion

The Torpedo Bat reflects real design thought. It might help certain hitters conceal flaws or reduce feedback. But performance isn’t about masking errors, it’s about solving them. Designing around late contact doesn’t correct timing. It just makes failure feel flush.

The strikeout era wasn’t built on mishits. It was built on misreads. Late decisions. Early commitments. This bat doesn’t fix that. If anything, it invites it.

The real cost isn’t comfort. It’s what comfort replaces. Whip, hard contact, and the ability to punish mistakes with violence. Those are the marks of elite hitters. When design trades that away for manageability, the result isn’t progress. It’s decay.