Why Statcast’s New Contact Point Data is Only Half the Story

By Ken Cherryhomes ©2025

Baseball’s understanding of hitting may have evolved… sort of. In a recent article on MLB.com, Shohei Ohtani contact point Statcast analysis author David Adler discusses how Statcast’s new contact point and depth data, set to debut on Opening Day 2025, will provide fresh insights into where MLB hitters make contact relative to home plate and their bodies. While this marks progress in recognizing the significance of contact points, the analysis remains tethered to the outdated paradigm of swing mechanics, overlooking the more critical role of timing. The article highlights Shohei Ohtani’s deep contact tendencies, framing them as a key part of his hitting success.

But is deep contact the reason for Ohtani’s success? And is his level of success the benchmark for all comparisons? While Ohtani is arguably the best all-around player in the game today, equating his deep contact tendencies with hitting efficiency oversimplifies what actually drives elite bat-to-ball skills. Some of the game’s best contact hitters with power—like Ronald Acuña Jr., José Ramírez, and Yordan Alvarez—thrive not because they make deep contact but because they consistently square up the baseball at optimal points in their swing arcs. Many elite hitters succeed with more forward contact depth, proving that deep contact is not a universal requirement for bat-to-ball precision or power.

In fact, for some hitters, deeper contact could be detrimental to their power production. Mookie Betts, for example, might optimize his power output by making contact slightly farther out front than Ohtani on the same pitch, hit to the same spot on the field. This allows him to fully optimize force transfer. A shift toward deeper contact would limit his ability to accelerate the barrel through the zone, reducing his capacity for hard contact and efficient launch mechanics. This further illustrates why deep contact is not a one-size-fits-all model for success.

Even among hitters analyzed in the article, the deep contact discussion lacks essential context. Freddie Freeman, for example, is featured as a deep-contact hitter, but his approach is uniquely tied to his high opposite-field hit percentage—a factor that naturally results in deeper contact points and a deeper contact point average. So, this raises a question: are deep contact tendencies a model for success, or simply a byproduct of chosen approach and/or pitch location?

While this new data point analysis is a step forward in data collection, the analysis in Adler’s article reveals a fundamental flaw in how hitting is evaluated and how success is attributed. The discussion of contact depth lacks key context, particularly how contact depth varies based on spray angle and pitch location. Additionally, the article leans heavily on mechanical interpretation, assuming that deep contact itself is a driving force behind Ohtani’s success rather than considering the more critical factor, elite decision and swing timing.

For decades, the industry has focused on swing mechanics, treating them as the primary determinant of success at the plate. But mechanics alone do not dictate performance. Timing does. Without understanding when a hitter makes contact, measuring where they make contact provides only half the story.

The Problem with How Statcast’s Data is Being Interpreted

MLB analysts are framing contact depth tracking as a mechanical insight, using Shohei Ohtani as their prime example.

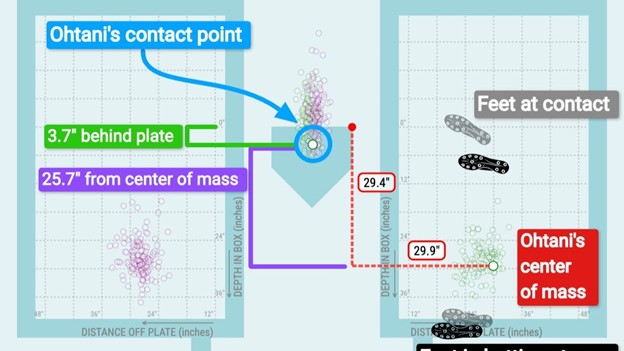

According to the article, Statcast’s data shows that:

- The average Major League hitter makes contact 2.4 inches in front of home plate

- Ohtani makes contact 3.7 inches deeper than the league average, meaning he lets the ball travel farther before making contact, which also means he is turning his swing over earlier than most hitters do

- The average MLB hitter makes contact 30.2 inches in front of their body

- Ohtani makes contact 25.7 inches in front of his body, nearly five inches deeper than average

The article attributes Ohtani’s deep contact tendencies to his all-fields approach and unique mechanics but does not analyze how his contact depth varies depending on pitch location and spray angle.

The Issue with Averaging Contact Depth

This leads to a misleading interpretation of the data, primarily due to aggregating all contact points into a single averaged number. Contact depth is not a static trait—it is a dynamic variable influenced by pitch location, spray angle, and approach. By averaging Ohtani’s contact points without separating pulled vs. opposite-field vs. center-field contact, the analysis fails to recognize that deeper contact is not necessarily where his most productive contact occurs.

For example, Ohtani is not pulling home runs with contact points 2.4 inches or less in front of home plate—and neither is anyone else. Pulled home runs require contact farther out front, where bat acceleration and force transfer are optimized. The deep contact points being averaged into his total do not represent the ones responsible for his hardest-hit balls.

Optimal Contact for Power is Not Deep Contact

Hard-hit balls and maximum power are typically produced when contact is made 12-17 inches in front of home plate—not deeper. Research from FanGraphs and other sources confirms that:

- The optimal contact point for home runs is around 10-17 inches in front of home plate, depending on pitch location and batter mechanics.

- Exit velocity peaks when the hitter meets the ball at the right point in their arc, which is farther out front, not deeper in the zone.

- Contact made too deep reduces angular momentum, limiting power output.

By averaging contact points across all pitch locations, swing types, and situational contexts, the interpretation fails to separate contact points based on spray angle. This creates a skewed comparison that does not reflect how hitters actually adjust contact depth based on pitch conditions.

If deep contact were the key to power, then the hardest-hit balls in the league would consistently come from deeper contact points—but they don’t. Instead, elite power hitters tend to meet pitches farther out front to optimize force transfer and maximize exit velocity.

Deep Contact is a Byproduct, Not a Model for Success

By failing to account for these established principles, the analysis overlooks the fact that deeper contact is not necessarily an advantage. Instead, it is a byproduct of approach, spray angle, and pitch location—not a universal model for success that applies to all hitters.

The Major Flaw: No Mention of Contact Depth Relative to Spray Angle

While the article acknowledges that Ohtani pulls home runs, it does not account for how his contact depth shifts depending on spray angle. Instead, it presents his deep contact as a universal trait rather than an adaptive one. I’ll expand on this further later in this article.

This oversimplification ignores a fundamental truth about hitting. Contact depth is not necessarily a fixed mechanical attribute—it is an interaction between mechanics and timing. Mechanics establish the range of possible contact depths based on the hitter’s swing arc, attack angle, and extension. Timing dictates where within that range the bat actually meets the ball, making it the overriding factor in determining success.

The point of view in the article may lead you to assume that a hitter can meet the ball at multiple depths while maintaining the same swing arc and still produce the same spray angle. This is not possible. For a ball to be hit to the same field from different contact depths, the swing arc must change. However, through its comparisons, the article appears to suggest that a specific swing arc model is optimal, which is not necessarily true and remains conditional on the hitter’s approach and physical attributes.

- A deeper contact point requires an earlier turnover of the barrel, shortening the circumference of the swing arc. This reduces the angular momentum of the swing, limiting force potential. That is why this approach is more suited for either very powerful hitters who can compensate with strength or contact hitters who sacrifice power for quickness. It is not universally applicable to all hitters.

- A more out-front contact point naturally expands the arc, increasing its circumference.

The depth-to-spray relationship is not static. Failing to account for these arc adjustments makes contact depth comparisons misleading. The article does more than just compare contact depths—it strongly implies that deeper contact is a model for success, positioning it as a key factor in Ohtani’s hitting approach. By doing so, it presents deep contact as an ideal mechanical model, rather than recognizing that Ohtani’s success is primarily a product of his elite strength, decision and swing timing.

This is why averaging contact depth without considering spray angle is flawed. A hitter’s pulled contact point is naturally farther out in front than their middle-of-the-field or opposite-field contact depth. If Ohtani pulls the ball 30 percent of the time and goes opposite field 40 percent of the time, his average contact depth is meaningless unless the distribution of his contact points is considered.

Additionally, not all hitters are physically capable of succeeding with a deeper contact approach. The only way to maintain deeper collision points across all pitch locations is to reduce the circumference of the swing arc. This limits the available space for bat acceleration, which is why only extremely powerful hitters like Ohtani and Aaron Judge can still generate elite exit velocities with this approach.

For most hitters, reducing swing arc circumference would result in weaker contact and a loss of adjustability. A broader arc provides more time to adjust to different pitch locations, whereas a smaller arc forces a tighter, more specialized hitting zone. If a hitter lacks the elite strength or bat speed to compensate, forcing them into a deep-contact approach would only lead to diminished offensive output.

Pulled versus opposite-field contact depths must be separated in analysis. Hypothetically, if Ohtani’s pulled home runs happen at an average depth of 27 inches in front of his body, but his opposite-field home runs occur at 16 inches, his average contact depth does not tell the full story. An elite power hitter like Mark McGwire’s approach highlights this flaw. While primarily a pull hitter, he varied his contact depth based on pitch location, meaning his deep contact was not universal but situational.

Statcast is measuring where hitters make contact, but MLB analysts are misinterpreting the data by failing to recognize what these points are actually telling us and why those contact points vary, and comparison is highly nuanced. Contact depth measurement relative to the batter’s center of mass is not just a function of mechanics; it is an adaptive process dictated by swing arc, the batter’s base width— which directly affects where their center of mass is positioned— timing, and pitch conditions. By focusing on mechanical interpretations rather than the influence of these key points, their conclusions about Ohtani—or any hitter—are incomplete, assumptive, and misleading.

The depth-to-spray relationship is not static. Failing to account for these arc adjustments makes contact depth comparisons misleading.

However, before even considering spray angle, the first issue is the way deep contact is framed as an advantage rather than a result. The comparisons in the article create the perception that Ohtani’s deeper contact is what allows him to generate elite power. But this overlooks a crucial reality of physics—deep contact is not inherently beneficial. In fact, the farthest-hit balls are not met at the deepest contact points. Ohtani’s power comes from his ability to generate elite force over shorter swing distances, not from simply making contact deeper in the zone.

The article does more than just compare contact depths—it frames deeper contact as a defining trait of Ohtani’s success, leading the reader to assume it is a model for optimal hitting. While it does not explicitly state that deep contact is the key to success, the way Ohtani is compared to other hitters implies that his deep-contact tendencies are not just unique, but inherently advantageous. This creates a misleading conclusion that deep contact is an ideal mechanical approach, rather than recognizing that Ohtani’s success is primarily a result of his elite strength and timing, much like it was for Barry Bonds.

This is why averaging contact depth without considering spray angle is flawed. A hitter’s pulled contact point is naturally farther out in front than their middle-of-the-field or opposite-field contact depth. If Ohtani pulls the ball 30 percent of the time and goes opposite field 40 percent of the time, his average contact depth is meaningless unless the distribution of his contact points is considered.

The Flawed Assumption: Deep Contact Equals More Power

While the article acknowledges that Ohtani pulls home runs, it does not account for how his contact depth shifts depending on spray angle. Instead, it presents his deep contact as a universal trait rather than an adaptive one. I’ll expand on this further later in this article.

This oversimplification ignores a fundamental truth about hitting. Contact depth is not necessarily a fixed mechanical attribute—it is an interaction between mechanics and timing. Mechanics establish the range of possible contact depths based on the hitter’s swing arc. Timing dictates where within that range the bat actually meets the ball, making it the overriding factor in determining success.

The article may lead the reader to assumptions that a hitter can meet the ball at multiple depths while maintaining the same swing arc and still produce the same spray angle. This is not possible. For a ball to be hit to the same field from different contact depths, the swing arc must change.

- A deeper contact point requires an earlier turnover of the barrel, shortening the circumference of the swing arc. This reduces the angular momentum of the swing, limiting force potential. That is why this approach is more suited for very powerful hitters and is not universally applicable to all hitters.

- A more out-front contact point naturally expands the arc, increasing its circumference and angular momentum, i.e., force.

The depth-to-spray relationship is not static. Failing to account for these arc adjustments makes contact depth comparisons misleading.

Why the Deep Contact = More Power Assumption is Wrong

Another critical issue with the analysis is the assumption that deeper contact leads to greater power production. The reality is that the balls hit the farthest are not going to be the ones met deepest.

- Maximum power requires full extension at the right point in the swing arc.

- Deep contact naturally shortens the swing arc, reducing angular momentum and limiting max exit velocity potential.

Ohtani doesn’t always cut off his swing. On some swings, particularly on pulled balls, he fully extends, meeting the ball farther out front. His longest home runs don’t come from his deepest contact points—they come from situations where he extends through the ball at an optimal point in his swing arc.

If deep contact were the key to power, then all the longest home runs would be hit at deep contact points relative to the batter’s body and the plate. But that’s not what happens. The biggest home runs occur when the hitter fully extends and connects at the optimal point in their arc, where the bat has reached peak acceleration and is moving through the most efficient force transfer zone.

This exposes another flaw in the way analysts are interpreting Statcast’s data. If they paid as much attention to failed contact as they do to successful contact, they would see this. Ohtani often turns his pulled swing over too soon, which limits his ability to fully drive the ball, but due to his elite strength, at times, still results in home runs. This isn’t a model that should be universally applied to all hitters—it’s an approach that works for him, given his unique power and ability to adjust his timing.

What the Article Fails to Analyze

- How Ohtani’s contact depth varies by spray angle

- His pulled contact depth versus his opposite-field contact depth

- The percentage of his swings resulting in pull versus opposite versus center contact

- How his timing shifts based on these factors

By failing to account for contact depth variations across different spray angles, the article presents an oversimplified view of Ohtani’s hitting tendencies. Statcast may be tracking this data, but without considering how contact depth changes situationally, the analysis risks treating an adaptive, timing-based process as a static mechanical trait.

The Hidden Variable: Contact Depth Measured from an Unstable Reference Point

The article relies on Statcast’s measurement of contact depth relative to the hitter’s body. The problem is that a hitter’s body is not a fixed reference point. These measurements are based on the batter’s center of mass, which introduces a major flaw in comparison. No two hitters have the same stance width, leg length, or posture, all of which affect where their center of mass is positioned at launch. A hitter with a wide stance naturally has a different center of mass than a hitter with a narrow stance, even if their actual contact depth relative to home plate is identical. Ohtani, for example, utilizes a wider base than many hitters, which means his measured contact depth relative to his body will naturally appear “deeper” than a hitter with a more compact stance—even if their actual bat-to-ball contact points are the same. This is why measuring and comparing contact depth relative to the batter’s body introduces unnecessary variability and skews comparisons.

No two hitters have the same base width, leg length, or posture, all of which affect where their center of mass is positioned at launch. A hitter with a wide stance naturally has a different center of mass than a hitter with a narrow stance, even if their actual contact depth relative to home plate is identical. If one hitter strides more than another, their contact point relative to the body will be different even if the swing’s interaction with the ball remains the same.

This raises a question. If base width, center of mass positioning, or physical proximity relative to home plate are not universal, how can the “in front of the body” measurement comparisons be valid? The answer is that it introduces variability that is not accounted for in the comparisons. Without a fixed reference point, conclusions drawn from these measurements may not be as meaningful as they appear.

The Flawed Assumption – Mechanics Shape Contact Depth, But Timing Dictates Success

Contact depth is determined by both mechanics and timing. Ohtani’s swing mechanics govern where he tends to make contact. His bat path, hand positioning, and extension influence his deeper contact tendencies. His cutoff extension contributes to why his average contact depth is deeper than other hitters. Timing does not dictate his contact depth, but it dictates whether or not that depth results in solid contact.

Timing dictates the success or failure of contact at any depth. Letting the ball travel does not guarantee quality contact. It just shifts the location where the bat meets the ball. If his timing is off, even with his optimal contact depth, he will mistime pitches, resulting in weak contact or swings and misses. Good timing makes any depth of contact an asset. Bad timing makes it a liability.

Statcast’s averaging method oversimplifies the contact depth discussion. Since Ohtani sometimes extends on pulled pitches, sometimes he cuts off his extension. These further skews averaging his contact depth and not considering spray angle further distorts the real picture. The relationship between contact depth, optimal outcomes and spray angle must be accounted for before drawing conclusions about a hitter’s success.

How This Creates a Blind Spot in Baseball’s Approach to Hitting

Statcast’s contact point tracking is a useful dataset, but without understanding timing as the governing factor, teams will be misled into making mechanical adjustments that do not address the root cause of performance.

The Takeaway: Mechanics Are a Byproduct, Timing is the Deciding Factor

MLB teams and analysts can analyze where a hitter makes contact, but without understanding when and why, they are only seeing half the picture.

Ohtani is not great because of his mechanical traits. He is great because of his ability to time the ball precisely and make consistently effective contact at his chosen depth. Until hitting analysis fully embraces this, the game will continue to misdiagnose the most important factor in hitting success.

The Next Evolution in Hitting Analysis

Baseball is beginning to integrate contact point tracking into its analytics, something I have been doing with the xFactor Hitting System for quite some time. But until analysts shift their focus to timing, teams will continue to chase mechanical solutions to what is fundamentally a decision-based skill.

Contact depth is not the key to success—it is merely a byproduct of swing arc, pitch location, and the hitter’s ability to make the right decision at the right time. Without integrating timing into hitting analysis, baseball will continue diagnosing symptoms instead of addressing the root cause of hitting success.